A Great Thriller

I’d like to tell you what I love to see in a great Thriller screenplay.

Firstly, we should define the term, but I’ll avoid a long-winded definition of Thriller; suffice it to say it’s “a story of high suspense.”

The high part is crucial to distinguish a Thriller as all good dramatic stories should feature some suspense. As Wells Root reminds us in one of the original (and best) books on screenwriting, Writing the Script (1980; Holt, Rinehart and Winston), even Romeo and Juliet is a suspense story: “Shakespeare told his love story in a sequence of…suspenseful scenes. And in resolving each crisis, he created another! Thus, the progressive tension increased until the play’s resolution, which was the lovers’ reunion in death.”

So let’s say that a Thriller absolutely depends on the increase of suspense, thrives on it; suspense is the spine of the story, the foundation of the narrative.

As a Reader and a filmgoer, I’d say a Thriller requires high suspense, high stakes, grave consequences, and it MOVES. Which brings me to what I consider to be the first and most important thing to have in a great Thriller screenplay:

A RELENTLESS PUSH FORWARD.

This can’t be stressed enough.

It has to keep moving and keep revealing new, crucial information and take surprising turns and keep moving some more and never stop until the shocking, yet inevitable end.

Okay, it can stop for a little breather every now and then.

In fact, it probably should, because an Audience/Reader needs some relief with so much tension (especially after one of those cringe-worthy scenes like the ear-severing in Reservoir Dogs or the semen-hurling incident in The Silence of the Lambs). This technique is aptly named…Tension and Relief! We need to stop and take stock of the situation a few times over the course of the story. But then we need to be grabbed, yanked and pulled back into the race. Don’t forget to keep it moving.

Raymond Chandler understood the need for break-neck pacing and hard-hitting plot points. Writing serials in detective magazines, there was no time for chit-chat, bub. You had to hook ‘em fast, get to the point, and leave ‘em hangin’ so they’d come back next month to find out what happened to their hard-boiled hero.

To this end, he typed on small pieces of paper, forcing himself to reveal a new piece of information on every page.

Now that’s pacing, palooka!

On that note, let’s take our own advice and continue with our checklist of excellent elements to feature in your great Thriller…

A great Thriller needs to have strong setups and payoffs, or what we call Cause & Effect, that create ESCALATING CONFLICT. You want to put your Protagonist up a tree and keep throwing stones. Don’t ever make it easier on them, you must make it harder. That could apply to any dramatic story, but it’s especially important in a Thriller.

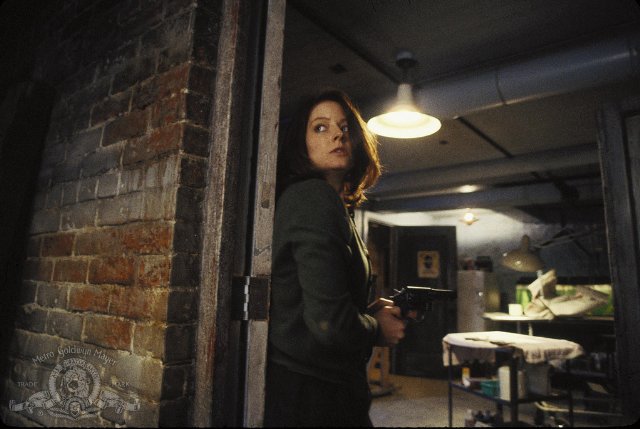

Think of little Clarice Starling in Lambs.

Trainee. Student. Diminutive in size, her male peers tower over her at every turn. Mocked. Hit on. Manipulated.

But with every setback she keeps fighting. She never gives up.

And she cracks the case and takes out the serial killer.

Like a strong Protagonist of a Thriller should do, Clarice Starling drives the story with her active decisions. This may seem like a logical element to have in any narrative, but in a Thriller it can get tricky when your hero, by nature of the “high suspense” situation, may be on the run, hunted, out of control, in search of a hidden truth, etc. But this does not mean they can only be reactive; they must be active.

Of course, there has to be something unique and dangerous that they are pursuing. A Great Thriller also needs to have a fascinating CENTRAL MYSTERY.

Who is Keyser Soze?

Who is the one-armed man?

What is Rosemary’s baby?

Who made the snuff film?

Can Clarice Starling use Hannibal Lecter to find Buffalo Bill?

You must keep the Reader turning pages, dying to find out the secret behind the big mystery.

I’ll tell you what else I love in a Great Thriller — when the script takes a HARD RIGHT TURN. Like in The Village when Joaquin Phoenix, our Protagonist, gets stabbed and thus taken out of the action. This hearkens back to perhaps the most famous Hard Right Turn in cinema — Janet Leigh, also heretofore the Protagonist of the story, being stabbed to death in the shower in Psycho.

How about the alien bursting out of the guy’s chest in Alien?

The first guy getting sucked into the sky in The Forgotten?

Neo getting jacked in to the Matrix for the first time via a port in the back of his skull?

The Trucker tells Kurt Russell he’s never seen his wife in Breakdown?

If you can make the Reader’s jaw drop by the Midpoint, you’ve got a great chance of getting that coveted “Recommend.”

Maybe the best Hard Right Turn I read on the job was The Truman Show by Andrew Niccol. In the original screenplay, we (the Reader/Audience) don’t know that Truman is on a 24-hour live television show until page 27! As the story is told from Truman’s POV up until that point, we learn this revelation along with him, and I can safely say it dropped us both on our asses; it was fantastic. Talk about jaws dropping.

But then it became a movie.

A big-budget movie starring Jim Carrey released by Paramount Pictures during a particularly gutless period of studio filmmaking in the 90s. And the studio decided that they couldn’t market the movie without giving away the premise, and, besides, the secret would get out immediately from word of mouth and it would doom the film, right? Apparently they hadn’t heard of a film named The Crying Game, and ironically there would be this little film called The Sixth Sense that would come out the next summer and prove them dead wrong (no pun intended).

So the horrible decision was made to rewrite the script so that it was apparent right away to the audience that Truman was living in a 24-hour TV show. This made the film essentially into a Drama, not really a Thriller. Or at least not as much of a Thriller as the writer intended it to be!

Still a decent film and a brilliant idea. But no longer a Thriller with an awe-inspiring Hard Right Turn. It really robbed a lot of the momentum and impact from the story.

But the lesson for the screenwriter is to look to the spec script, not the film, for the true, most pure and high-suspense, high-stakes structure of this story. The spec script for The Truman Show sold for a nice amount, made a huge splash in the industry and established Niccol’s career. The lesson for us all is to shock and surprise that Reader…even if you don’t think it will ever make it on film.

I remember my supervisor at Jonathan Demme’s company telling me about Andrew Kevin Walker’s new spec screenplay, titled 8mm. He said “It makes Seven look like a Disney film.” Now THAT’s a spec that’s got buzz!

So go for it. And don’t be afraid to go all the way.

Why? Because not only does Drama = Conflict, but Hollywood is filled with thousands of bored workers reading the same old plot turns and story mechanics — pull the seat out from under them and they’ll love you for it.

Trust me. You may think they’re looking to say “no,” but what they’re really doing is looking to say “yes.”

They also want you to know and respect your genre and its core audience. So study up on Thrillers; make sure to watch and analyze a bunch.

It helps to stay true to your genre, which means first you need to understand the genre. And a Thriller is its own animal with its own conventions that I believe should be respected and adhered to and the writer needs to have the guts to go to the extremes with their story decisions and suspense-building techniques.

Let’s go back to Wells Root for some of those techniques and then we’ll look at two recent films which in my opinion did not respect their genre…

Wells Root’s “Methods of Suspense” —

Conflict — again, the stuff of drama. Load it up, keep it coming and make it “aggravate,” or change form.

Master Antagonist — a fascinating, brilliant, powerful villain.

Compounding Suspense — making it get worse and worse, escalating the conflict, heightening the tension.

The Dreadful Alternative — high stakes, grave consequences. What will happen if the hero does not save the day?

Audience in Superior Position — it often heightens the tension when we realize the hero is walking into a trap but they are oblivious to their situation. This is optional, depending on your story structure. It may work better for us to only know what the hero knows (as in the original draft of The Truman Show), or maybe know less than the hero (Audience in Inferior Position). It’s your call.

Unexpected Complication — it’s always best to surprise us, to subvert our expectations, not meet them. A good Thriller will always continue to catch us off guard.

Crisis Opening — lighting a box of dynamite in your opening. Throwing us, and your Protagonist, immediately into the fray.

These are powerful dramatic tools for building your Thriller.

One of the things I love about the Thriller as a genre is that it features so many great Structural Archetypes and Antecedents.

So many classic Story Engines that work so well in a narrative.

The “innocent man on the run” in films like The Fugitive or North by Northwest.

The “sympathetic victim ensnared in a trap” of Body Heat, Vertigo, Malice.

The “good cop manipulated by the femme fatale” of Basic Instinct, Sea of Love.

The “wronged man must take revenge” of Gladiator, Payback.

The “serial killer hunt” of M, Dirty Harry, The Silence of the Lambs, Kiss the Girls, Seven, Zodiac.

The “civilized man trapped in an uncivilized society” of Deliverance, Straw Dogs, The Wicker Man.

The “nefarious plot gone wrong” of Dial M for Murder, A Perfect Murder, Strangers on a Train, Fatal Attraction.

The “seemingly innocent man with a buried secret” of A History of Violence, Insomnia.

The “curious observer sucked into a conspiracy” of Rear Window, Three Days of the Condor.

The list could go on — I haven’t even touched on Action Thrillers (Die Hard), Courtroom Thrillers (The Verdict), Spy Thrillers (The Bourne series), Men on a Mission Thrillers (The Dirty Dozen) or Kidnapping Thrillers (Ransom, The Way of the Gun).

I bring up these Thriller story types because I have read too many screenplays in which the writer did not know they were using one of these forms, or they should have been using one of them, considering their main dramatic elements, what I call their Story Map.

A screenwriter must know what TYPE of story they’re telling, what KIND of machine they have built and how it works traditionally and how they may be modifying it.

I’m definitely of the camp that believes you need to understand the traditional forms before you can experiment successfully with them. Too often screenwriters are ignorant of the classic forms.

This happens in produced films, as well.

Two somewhat recent examples, in my opinion, of films that didn’t know or respect the Thriller genre and its conventions, were the remake of The Manchurian Candidate (original novel by Richard Condon) and A History of Violence, which was adapted from a graphic novel by John Wagner and Vince Locke.

The Manchurian Candidate seeks to update the story of a brain-washed, Communist assassin to our post-9/11 political landscape. Which is fine, and they did a good job of making that modern political world believable down to the last detail, but the movie went one step further by seeking to add a serious theme with Denzel Washington’s portrayal of a Gulf War combat vet with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. It felt to me like they were trying to justify the outrageous comic-book style assassination plot with a serious theme. But this IS a comic-book style thriller; that’s the fun of the story! The original film is famous, and successful as a Thriller, because of the Hard Right Turn wherein the old ladies playing solitaire in the recurring flashback become Communist military officials — and then of course the climactic reveal of the true target. This is an over-the-top spy thriller, not a serious meditation on the disastrous effects of war. In this regard, by spending so much time on the wounded psyches of the Denzel Washington and Liev Schreiber characters, I felt the film missed its mark.

Similarly, I felt that Josh Olson’s screenplay and David Cronenberg’s film of A History of Violence abandoned its own source material and the result was a muddled patchwork of elements. The film seems to throw out almost everything about the original story save the setup and embraces more of the “supersoldier archetype” of a film like First Blood rather than focusing on the “man with a buried secret” form of the graphic novel. Cronenberg also weaves in sexual themes that serve to pull the film away from its classic Thriller roots.

These examples highlight the modern need for a film to feel real for the audience. In a Thriller, the most important aspect to be real is the THREAT. It needs to be real…scary! Or at least, real tense. We need to be on the edge of our seats to find out if the hero will verify the truth or origin of the threat and ultimately overcome it.

It’s important to understand the difference between realistic and real. A screenplay and film absolutely needs to be real and truthful…but only unto itself and its own established world.

Star Wars feels real…for a galaxy, far, far away. So does Minority Report, a Science Fiction Thriller set in a near future Washington D.C. But neither film is realistic in the sense that it could happen in our modern world. The reality exists convincingly in the dramatic world of the story.

Another Shyamalan film, Signs, did a convincing job of showing a realistic take on an alien invasion from the perspective of one man and his family on their farm. The story is a progressive series of events that serve to convince us the aliens are real, not fantasy. This narrow POV approach was applied to Spielberg’s War of the Worlds, but they made the choice to reveal the threat much sooner. The result, ironically, was that the film felt realistic but the emotions did not feel real. Spielberg didn’t follow his own Jaws “one-hour rule” and chose to show the threat early on in War of the Worlds — this and the lack of a strong climax crippled potential for suspense.

Some recent films toy with the idea of reality to varied levels of success. The Japanese horror drama Audition features a final act that keeps cutting between dream and reality, to the extent that it becomes impossible to distinguish the two. For me, this totally undercut the reality of the story, which was a nicely established story of suspense, and I ended up feeling discouraged and unsatisfied.

We follow the Protagonist in how we feel. If my hero is not convincingly in danger, I won’t feel in danger.

The film Identity sets up a compelling mystery of murders with multiple suspects all in one location. But the ending twist reveals that all of these characters exist in the head of a killer on death row. It was all a fantasy. Not real. This hook totally deflates all of our expectations for a shocking yet satisfying ending.

The “family in a haunted house” film The Others reveals they were the ghosts, and it works, because even though it’s a ghost story, which is not realistic to our experience, it still felt utterly real in the film.

As you consider these films, you may be feeling the need to find a HOOK that sets your Thriller screenplay apart.

The hook may be a situation, or it may relate to your Protagonist’s unique decision, like in Ransom when Mel Gibson decides to offer the $1 million ransom as a bounty on the head of his son’s kidnappers.

This hook should be highlighted in your all-important logline. If you have to give away the ending to reveal your hook, if there’s no other way, then give away the ending in the logline. Hopefully the Creative Exec or Assistant who reads your logline won’t show it to the Reader who writes the coverage, but even if they do, a good Reader is able to put themselves in the position of a cold audience member for that first read.

Personally I like to use the following construction for a logline:

An engaging protagonist must struggle against tremendous odds in pursuit of his/her goal.

That sentence tells us our MAIN CHARACTER, their GOAL and the MAIN DRAMATIC CONFLICT they face in trying to achieve that goal. You may also want to add WHERE or WHEN this story occurs, your unique setting.

Thrillers can be tricky to capture in a logline. You may find that this structure fails you in terms of presenting your high-concept hook and the unique way in which you reveal it. You may have to play with the order and the elements a bit.

I hope I’ve given you some insights into the genre that will fuel you to nail a fantastic logline that generates a nail-biter of a screenplay and film. For more detailed analysis and lessons from the pros, please see my Story Maps book series, available now in a special bundle offer in the highest-resolution PDF format…

The two Story Maps e-books available in this special offer include Full Story Map analyses of 19 hit movies, primarily from the last decade.

The two Story Maps e-books available in this special offer include Full Story Map analyses of 19 hit movies, primarily from the last decade.

These successful films are great examples of professional screenwriting in many different genres and budget levels aimed at varied audiences. I stand by each title as a strong example of its genre and as a primer to learn the screenwriting craft at the level that you need to be: the “submission ready” tier that makes a good script into a GREAT script.

Good Luck and Happy Writing!

Daniel Calvisi

Related: Free Story Map sample: Black Swan

Related: Free Story Map sample: Raiders of the Lost Ark

Related: Free Story Map sample: The Wrestler

“Dan has a no-nonsense approach to screenplay analysis that cuts through the bull and delivers the goods. A must read for serious screenwriters.”

“Dan has a no-nonsense approach to screenplay analysis that cuts through the bull and delivers the goods. A must read for serious screenwriters.”

-J. Stephen Maunder, Writer/Director

“…as much as an analysis of Nolan the filmmaker as it is an analysis of story structure within his films.”

-Script Magazine

What about the character arc? I certainly hope it is not necessary, because I am writing a thriller that does not have one. This is causing me anxiety as I feel I should put one in, in the next draft.

Good site! I’m a huge thriller and action fan, love Se7en and Hitchcock. I’m going to look at your other posts.