Is Inception better than The Dark Knight Rises? (Inception Podcast)

Which film can be called Christopher Nolan’s masterpiece? His Dark Knight trilogy is truly an amazing accomplishment, with The Dark Knight shining tall as the greatest of Nolan’s Batman films, in my humble opinion, but one must consider that Inception was all Nolan. His concept, his script, his direction. It’s a complicated movie and a complicated screenplay structure, so Rob Rich and I took time out to discuss it in the latest episode of our Story Maps Screenwriting Podcast.

Listen to the Inception Podcast:

[audio:http://traffic.libsyn.com/storymapspodcast/Episode_Four_-_Inception_Podcast_1.mp3]

Back to the masterpiece question. Let’s compare Inception to Nolan’s other films.

The first notable comparison lies in the source material. As mentioned, Inception is an original screenplay by Christopher Nolan — it is not based on an established character or universe (e.g., the Batman trilogy), a book (The Prestige), an existing film (Insomnia) or a short story by Jonathan Nolan (Memento). The great David S. Goyer wasn’t there to polish the edges of Nolan’s screenplay, and (gasp) there was no pre-existing brand for the studio to market. If I am not mistaken, even Nolan’s first film, Following, was based on a short story by his brother, even though the imdb listing for the film does not say so. So we need to give props to Chris for breaking out the Underwood and the scotch and busting his ass on this one (and while he was still in post on The Dark Knight? Sheesh, this guy’s got a lot of energy.).

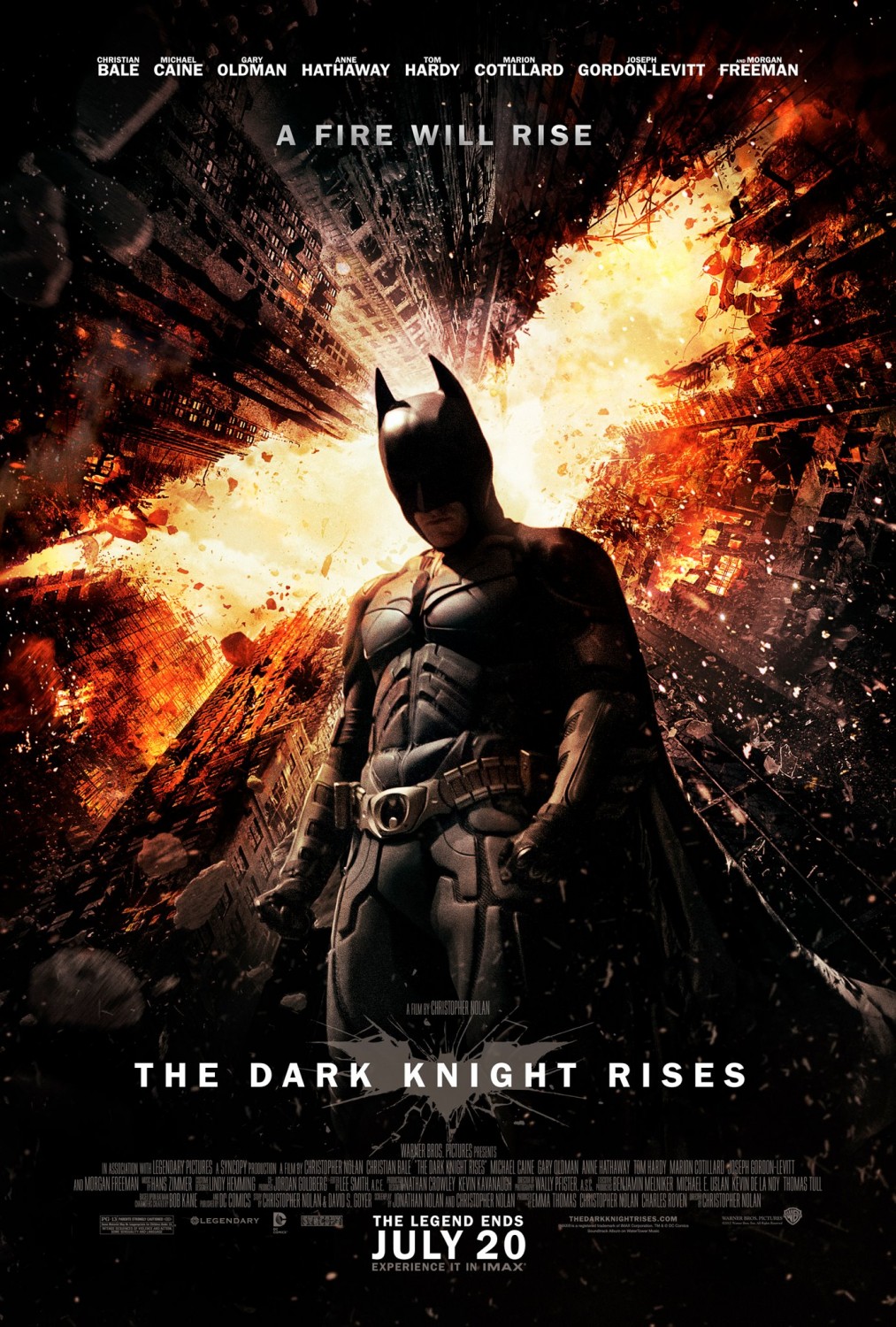

Structurally, the two films are similar, but there are key differences. As you can see in our first-draft story map of The Dark Knight Rises, there is a very clear four-act plot structure (Act 1, Act 2-A, Act 2-B, Act 3), even though it’s a longer film than Inception. One could interpret TDKR in five acts, as we have done with Inception, although Inception is unique in that its final act is so clearly linked to the “levels” of the dream world, so it’s almost a mathematical structure as we progress down the levels. Inception just feels like a more defined five act story to me than TDKR. (Note: I eventually settled on a four-act Story Map of Inception, whereas Rob Rich still argues a five-act structure. You can find both of our maps in our e-book, Story Maps: The Films of Christopher Nolan.)

TIME IN INCEPTION AND THE DARK KNIGHT RISES

Nolan always plays with time in his films — he rarely uses a straightforward narrative, almost always a fractured one — even in Insomnia, his most linear narrative, he uses quick flashbacks at times to show the villain’s depravity. The progression of time, both in the pacing of the film (for the audience) and the timeline of the story (for the characters), is especially crucial in Inception and The Dark Knight Rises. Elvis Mitchell’s interview with Christopher Nolan on his NPR podcast “In Treatment” opens with a discussion of Nolan’s use of time, touching on topics like cross-cutting, passage of time both onscreen and off, and the “ticking time clock” device (Interestingly, Nolan recently read that Fritz Lang claimed he invented the countdown (10, 9, 8, 7…) in Metropolis. Anyone ever heard that?).

NOLAN: In The Dark Knight Rises, we try and tell a very long time span, for this genre, and then we try and really compress it and accelerate it toward the end, so time is very elastic in the film.

I’ll leave it up to you to decide if he was successful or not with the pacing of TDKR. To begin with, Nolan chose to set TDKR eight years after the end of the The Dark Knight, to most dramatically express the decay of Bruce Wayne’s body and mind and the change in Gotham since the “war” with The Joker and the passing of The Dent Act, which turned crime-infested Gotham City into an orderly utopia (so to speak). Personally, I can’t help but wonder why he couldn’t have made it five years, or even three years — eight just seems so excessive to me — but that was his choice. He also chose to create a five month long span of time for the second act. Many have criticized the logic of Bruce Wayne flying across the world in a few days (and with no money!), but if you follow the time set forth by characters in the film, there is actually a three week time span from when Bruce escapes the pit and when he arrives in Gotham for the final fight. I’d like to think that with his skills and contacts, he could find himself a plane ticket and fly back home with enough time to spare to set up a fiery bat symbol on the bridge, thus motivating Bane’s line, “Impossible,” which seems kind of odd, considering that Bane put him in a prison and showed him how to escape, but we won’t dwell on that narrative choice.

In Inception, time is compressed from the getgo as the story moves quickly to the midpoint when they launch the mission into Robert Fischer’s subconscious. And once they begin the mission, it moves even faster. But Nolan also throws in mentions of extremely long time spans, with the limbo sequences, so the story spans a greater time period even as it accelerates at a breakneck speed.

In short, both films have great pacing challenges, with a required mix 0f fast-paced sequences with ticking time clocks, and slower passages of time that must convey a much more languid tone. Nolan comments on this when he compares his films to a piece of music:

NOLAN: In an action film, you have to view it as a piece of music, so you want the crescendos in the right place. You can’t not have those. So the quiet moments start to be influenced by the loud moments. It’s very easy with action cinema to be dismissive of the fireworks, but they are doing something powerful, and you get to use that.In the case of all these films, you get to the last two reels, and it’s relentless. Hans Zimmer’s music is almost identical in the final act of TDK and TDKR. They become musicals.

DUALITY OF HERO AND VILLAIN

No great hero is complete without a great villain. There must be an external/action connection and an internal/personal connection between the two. In Inception, it’s interesting how the villain, Mal, plays a role both in Cobb’s downfall (she set him up for murder in the “real world” and she’s always lurking in his “dream world.”) and his salvation (she is the mother of his children that he so desperately wants to see). The Batman character, created 73 years ago, has always had colorful villains that often represented sides of Bruce Wayne’s personality. Nolan comments on the duality of hero and villain:

NOLAN: One of the most interesting things you can do for a protagonist is to set a mirror in front of them. If the antagonist doesn’t get them at all…is from another planet (so to speak)…shares none of their values in any way, they’re not going to be as threatening. I really enjoy telling stories where the protagonist is being undercut by the villain; the villain is really getting under their skin because they share knowledge, they share the same point of view in some bizarre way. The more bizarre in which you can find that relationship, the more fun you can have with it.

If you can set up a protagonist and antagonist relationship with two people who have a very interesting, contrasting view of the world, and so forth, you start to create a great deal of anticipation about what they would say to one another, if they were in the same room. In The Dark Knight, that would be the interrogation scene, which was one of the first scenes we shot with Heath and Christian and Gary, and it was amazing to be a part of it. If you’ve done the rest of the story right, when you get to the end you don’t need an enormous amount of technique, you just need interesting characters talking about things that you want to know the answer to.

EXPOSITION – ESTABLISHING THE “RULES” OF THE STORY

Both films have huge amounts of exposition to communicate to the audience, and it can get frustrating with how much of it is explained in dialogue. I can’t help but think “SHOW, don’t tell!” at various points in both TDKR and Inception, and honestly there are moments in both films where I expect more out of the screenplay than generic “on the nose” lines of dialogue. Even so, there are a lot of dramatic “rules” to be established to allow for the proper setups and payoffs to motivate the action set pieces and escalate conflict, and they’re making these films for a global audience, so you can’t blame a certain level of obviousness. Unfortunately, there are also some logic gaps in both films — it’s up to you to decide if you can chalk it up to a reasonable amount of suspension of disbelief or poor storytelling.

SYMBOLS

Bruce Wayne spends the first half of Batman Begins in search of the symbol with which to strike fear in the hearts of his enemies, and that symbol turns out to be his greatest childhood fear: the bat. Goyer and the Nolans did an excellent job of re-interpreting that classic backstory for a new generation. In The Dark Knight Rises, one of the elements I enjoyed the most is how they supported the theme of Batman as an anonymous symbol of hope and justice. Bruce Wayne’s goal with “The Batman” has always been to represent an everyman of Gotham City, so that an average citizen may look at him and think he could be anyone, he could be me — this is shown in pure and simple form by the white chalk symbol of the bat scrawled by a child, the first time that color has been used to symbolize Batman. The symbolism is clear: Batman must give up the dark avenger and become the white knight of Gotham City.

Ultimately, this theme serves to answer two of our biggest questions we have as we begin the third and final chapter of this saga: Will Bruce Wayne live or die? Will Batman’s identity be revealed? It’s not about Bruce Wayne as the hero…it’s about Batman as the hero. This is a crucial distinction, as it serves to justify Bruce’s final action of faking his death when he takes the nuke out to sea. Even after death, the people of Gotham must not know that Bruce Wayne was Batman, so that he remains a symbol that will last for all time, and becomes a mantle that anyone can pick up and assume, which is what happens at the very end when John “Robin” Blake inherits the Bat Cave, launching a new era of crime fighting in Gotham City.

In Inception, you have the device of the totems, a visual device that links the real world and the dream world. If you want to debate the question of the entire film being Cobb’s dream, then you must look at the use of his totem, the spinning top, because it was originally Mal’s totem, and due to Cobb’s use of inception, she became unable to differentiate dream from reality. The idea may be that the totem tells dream from reality, but what if the totem itself isn’t real? And if it is real, is it a clear harbinger of doom for Cobb, as it was for Mal?

Supporting characters also have objects of their own, like Robert Fischer’s pinwheel toy, which represents his father’s absence during his childhood. There are other symbols like mazes, staircases that go nowhere, or even the faceless children that always wear the same clothes.

SCALE

The Dark Knight Rises had the biggest budget of any Christopher Nolan movie to date, but that doesn’t mean it has the largest size and scope. If you think about it…well, okay, it does. It’s a “bigger” movie, in terms of the size of the sets, action pieces, number of extras used, cgi, etc., plus it spans more time and there are more lives at stake.

But size doesn’t matter, does it?

That’s for you to decide.

You didn’t actually think I was going on record as to which film is better, did you?

Good Luck and Happy Writing,

Dan

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!